“Beginning in the middle of the 19th century, the leisure class grew infatuated with a particular type of healthy getaway: the water cure. By the 1850s, a constellation of spa villages had emerged across 20 states. By 1930, the country had over 2,000 hot- and cold-spring resorts.”1

Places like Michigan’s Battle Creek Sanitarium became world-renowned in the late 1800s for their focus on diet, exercise, hydrotherapy, massage, and myriad other therapeutic treatments.

East Tennessee was no exception to this burgeoning interest in what today we could call “wellness culture.” By the mid-to-late-1800s, there were at least three health resorts in the Smoky Mountains region where well-to-do travelers would get away to “take the waters.” Henderson Springs, in Sevier County, first saw use as a health retreat at least as early as 1830, followed by Montvale and Alleghany Springs in Blount County.2

Those Knoxvillians who did not have the time or means to get out of town and visit a health resort still desired a local establishment where they could enjoy steam baths, massages, and other treatments that were thought to improve health and cure a wide range of illnesses.

Raymond Ayres Lovell was born on November 10, 1876 in Wisconsin. His parents, Edwin O. Lovell and Ellen Ayres Lovell were both from the town of Oakham, Massachusetts, but in his early childhood, Raymond and his family lived in Milwaukee. Edwin and Ellen separated and divorced around 1884-1885. Edwin remarried, and it seems their children stayed with Ellen, including Raymond, who would have been about 8 or 9 years old.

In 1889, when Lovell was only about 13 years old, he and his older brother, Arthur I. Lovell, lived in Battle Creek, Michigan and worked as laborers at the Battle Creek Sanitarium. Arthur would have been about 22 years old at the time, and would have presumably acted as a guardian of sorts to his younger brother, as they were the only members of their family in Battle Creek.

Arthur and Raymond returned to Milwaukee around 1891, and in 1892, the teenaged Raymond was working there as a milk peddler. The Lovell family’s whereabouts become unclear in the mid-1890s, and they may have left Milwaukee for parts unknown.

However, Raymond’s experience at the Battle Creek Sanitarium must have been memorable enough to draw him back, because by 1897, he had returned to Michigan and was working as a helper for the Battle Creek Sanitarium Health Food Company. Begun as part of the sanitarium, the health food company was famously spun off into what later became the Kellogg company, known worldwide for its cereal products.

John Harvey Kellogg, “a Seventh-day Adventist and vegetarian... became superintendent in 1876 of the Seventh-day Adventist Western Health Reform Institute, which then became the Battle Creek Sanitarium, located in Battle Creek, Michigan… Kellogg developed numerous nut and vegetable products to vary the diet of the patients, including a flaked-wheat cereal called Granose and cornflakes. Although cornflakes were not new, they had never before been presented as a breakfast food. In 1898 Kellogg and his brother W.K. Kellogg founded the Battle Creek Sanitarium Health Food Company to handle the production of cornflakes and other foods for sanitarium patients. In 1906, after a dispute over the distribution of their cornflake cereal, W.K. Kellogg formed his own cereal company, the Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company (later renamed Kellogg Company).”3

Raymond Lovell at his daughter Dorothy Lovell Charland’s wedding, August 10, 1937. (Knoxville Journal)

Delia Eliza Walker was born around 1877-78 in Minnesota. Her father, Bradford T. Walker, was from Canandaigua, New York and her mother, Delia R. Walker, was from Connecticut. However, in the 1880s she and her family lived in Waltham Township, Mower County, Minnesota, a small farming community about 95 miles due south of Minneapolis.

The family was still living in Waltham Township in 1885, but sometime prior to 1900 they had moved to Tennessee, settling in the Rhea County town of Dayton. Bradford Walker was employed there as a drayman, delivering freight on a horse-drawn wagon called a dray. Delia was inspired to become a nurse when her mother read her a story about a nurse “and her life of loving service for suffering humanity.” She imagined herself being a missionary nurse in India, and around 1894 she undertook four years of missionary nursing training. Around mid-1898, Delia went to Battle Creek, Michigan for three-and-a-half more years of training at the sanitarium.4 By 1900 she was working as a professional nurse, and although she was back in Tennessee at her parents’ home just long enough to appear in that year’s census of Rhea County, she went back to the sanitarium soon after.

Delia Walker must have met Raymond Lovell in Battle Creek, as by 1901 they were both working as nurses at the sanitarium. They were married on December 27, 1901 in Battle Creek. However, they may have already moved to Superior, Wisconsin by that time and only went back to Battle Creek to be married. “Lovell, Raymond A, nurse,” appeared in the 1901 edition of the Superior, Wisconsin city directory. It’s unclear where they had been living when they married- Battle Creek or Superior- and when they relocated to Wisconsin to continue working as nurses.

While the Lovells did not stay in Superior very long, what is clear is that they were still living there on November 20, 1903, when their first child, Frank Bradford Lovell, was born. Less than two years later, they had relocated to Knoxville, Tennessee.

Why Knoxville, a place to which they seemingly had no prior connection? A likely explanation is that Delia Walker Lovell’s family were still living in Dayton, not too far from Knoxville- the Walkers appeared on the 1910 Rhea County census- and she wanted to be near them. Interestingly, it’s possible that they had initially intended to move to Chicago, Illinois, before going to Knoxville instead. The 1905 city directory for Superior, Wisconsin actually featured the directory listing “Lovell Raymond A, moved to Chicago, Ill.” However, there is no known evidence that the Lovells ever lived in that city, and Chicago’s loss was to be Knoxville’s gain.

The first documented appearance of Raymond A. and Delia Lovell in Knoxville was in the 1905 city directory, although they may have been in town as early as October of the previous year. On December 5, 1905, the Knoxville Sentinel ran a brief story about the Lovells, saying “October 13, 1904, Mr. and Mrs. Lovell started their great work by engaging as nurses.”

After their arrival in Knoxville, they had wasted no time in setting up their new business, as the 1905 directory lists Raymond as manager of “Sanitarium Turkish Bath parlors,” and Delia was listed as “trained nurse.” They rented a residence at what had been 1400 Forest Avenue, in the Fort Sanders neighborhood. The approximate present-day address is 1410 Forest Avenue, but the house where they rented is gone.

On February 5, 1905, the Lovells opened their first Knoxville Turkish bathhouse business downtown, on the first floor of the Navarre Flats building at 510 Walnut Street. This building was also known as the New Sprankle building. It was located on the east side of Walnut Street, between Clinch Avenue and Union Avenue; today that spot is a parking lot. They advertised their services in local newspapers as early as April 7, 1905. In a nod to the place where they had received their training, and as an extension of that institution’s philosophies, by June of that year the Lovells were calling their location “Branch Battle Creek Sanitarium Treatment Parlors.”

Lovell’s Turkish baths advertisement, 1905 (Knoxville Sentinel)

Navarre Flats, 510 Walnut Street, Knoxville, circa 1905 (Calvin M. McClung Historical Collection)

The original Battle Creek Sanitarium in Michigan had been founded on philosophies of health espoused by the Seventh-Day Adventist Church, and Raymond and Delia Lovell were also affiliated with this same church. On April 16, 1905, the Knoxville Journal and Tribune reported that “the Seventh-day Adventists have evidently come to Knoxville to stay. In view of the fact that they have recently built their first church building, a neat structure, in this city… and that they have established permanent sanitarium treatment parlors in the new Sprankle building on Walnut Street, it may be proper to publish a brief statement concerning the teaching and work of this denomination.”5

At the treatment parlor on Walnut Street, available services included three types of baths- Turkish, electric light, and tub-and-shower- plus massages, shampoos, something called “salt glow,” which may have been a type of exfoliation treatment, and various water sprays. The clientele were separated by gender; ladies were welcome between the hours of 8 a.m. and 5 p.m., and gentlemen’s hours were 5 p.m. to 11 p.m.

The business flourished on Walnut Street for about four years, and it eventually also opened a dining hall offering “Battle Creek Sanitarium Health Foods” in addition to its Turkish baths and massages.

The entrance to Lovell’s treatment parlors at 510 Walnut Street, circa 1905. “Electro Turkish Baths; Sanitarium Treatment and Massage Parlors,” reads the free-standing sign. The sign above the door reads “Battle Creek Sanitarium Health Foods. Nurses Exchange.” (Calvin M. McClung Historical Collection)

“Recently opened suite 45, Navarre Flats,” read a 1906 advertisement, “is but a PART of the working out of the plans to offer the citizens of Knoxville and vicinity rational methods of living. One year ago, February 5, definite steps were taken to offer to the thinking people of Knoxville- in the opening of the Sanitarium Treatment Parlors- accommodations for rational TREATMENT, such as is obtained by the use of hydro-therapy and massage, employed for so many years at the world renowned Battle Creek (Mich.) Sanitarium. Mr. and Mrs. R.A. Lovell, trained nurses of the Battle Creek Sanitarium, are in charge of this work. The success attending their efforts the past year encourage them to renew their efforts to acquaint the people of Knoxville with ‘The Simple Life.’”

Raymond’s and Delia’s second child, daughter Dorothy Miriam Lovell, was born on October 6, 1906. During this time, the family changed residences several times. In 1906, they had left Forest Avenue and were living in the Navarre Apartments, at the same 510 Walnut Street address as their business. In 1907, they were back in the Fort Sanders neighborhood at 1215 Highland Avenue. 1908 saw them move out to the Park City neighborhood, at 2023 Jefferson Avenue.

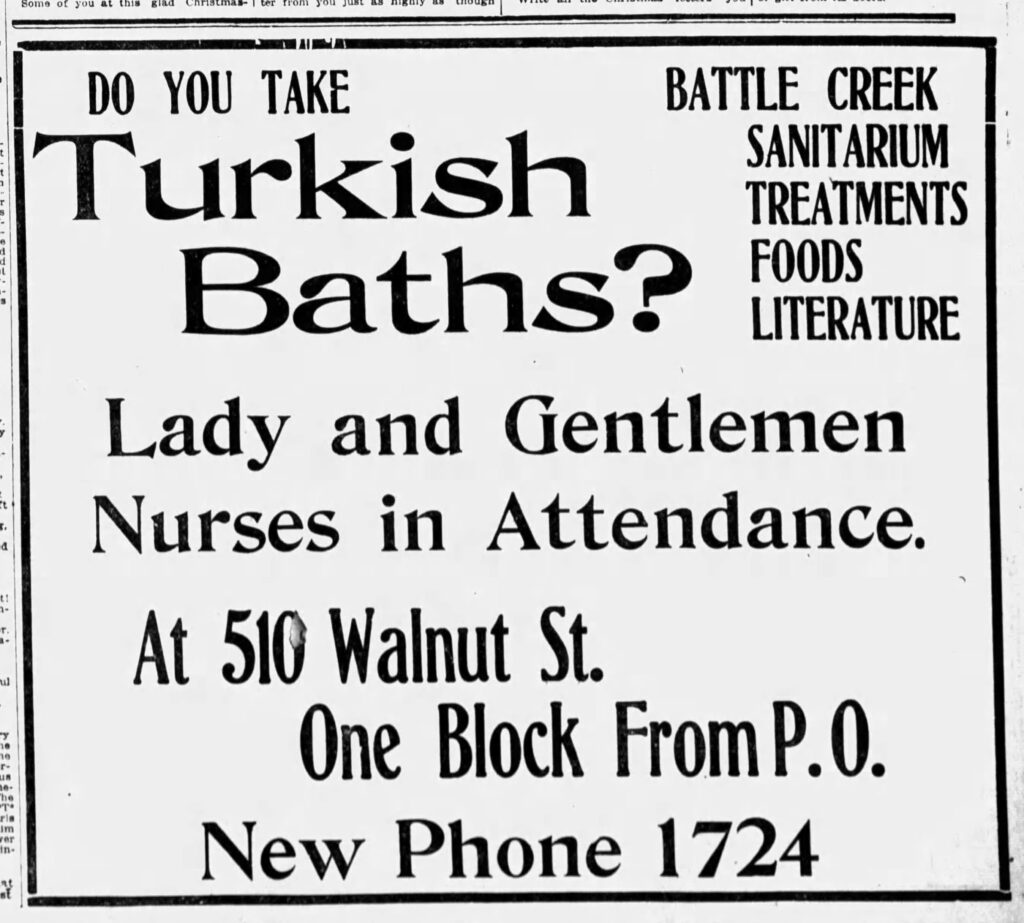

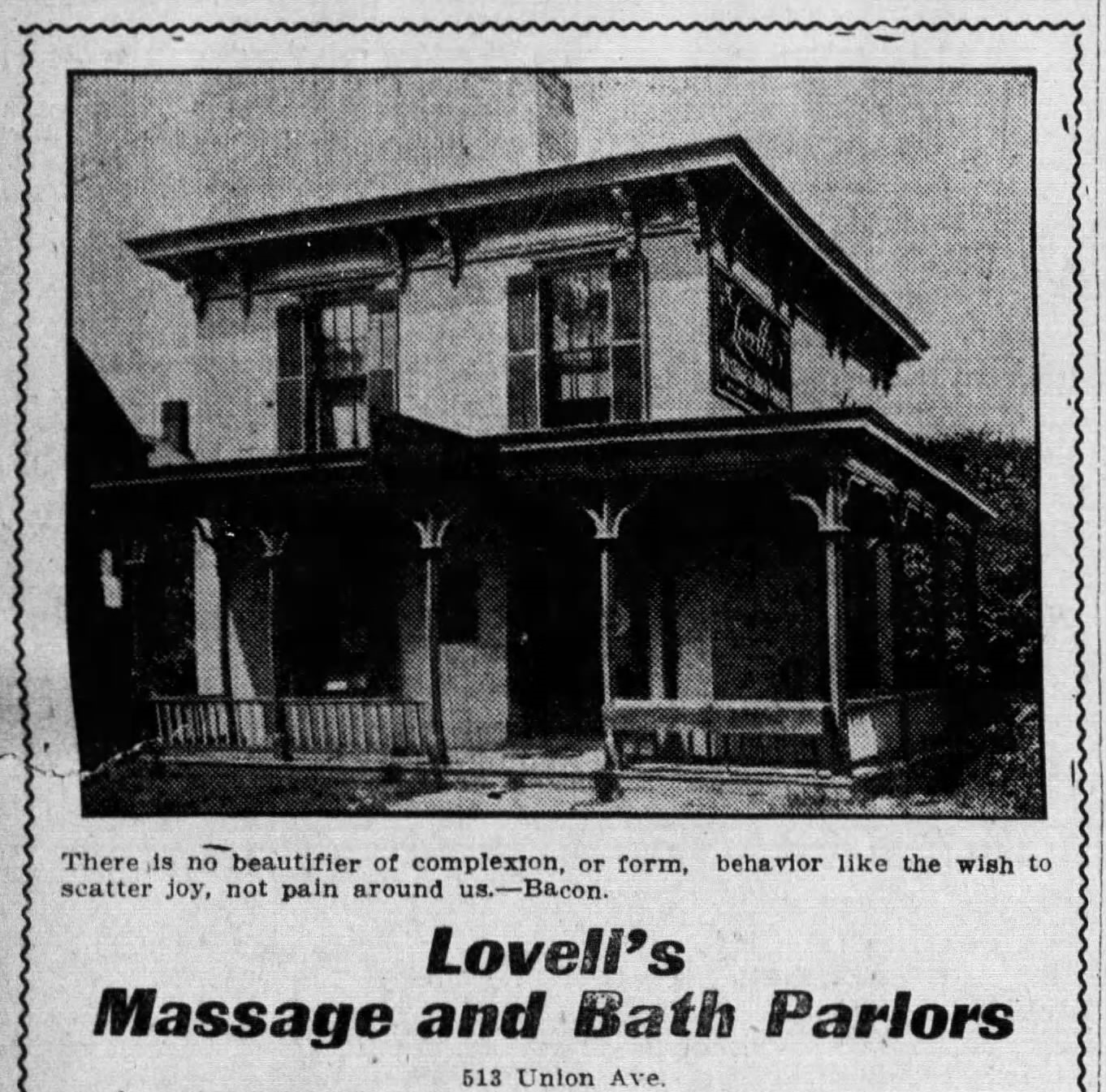

The following year, Raymond and Delia Lovell made a big change in their business that would soon affect their home life, as well. In June 1909, the firm of Doll, Mynderse & Brownlee advertised a building available for rent downtown at 513 Union Avenue. The first hint of an impending move was in July, when space in the New Sprankle building, “formerly used by Dr. Lovell,” was also advertised for rent. (It’s not clear whether either of the Lovells actually told anybody that they were doctors, or if somebody just assumed that one or both of them were, based on the type of work they did.) The Lovells made it official on August 24, 1909, announcing that the Turkish bath and massage business had moved from 510 Walnut Street to 513 Union Avenue. The new location was between Locust and Walnut Streets, on the west side of what had been a Girls’ high school around the turn of the century and what later became Boyd Junior High School. The Daylight Building later replaced the junior high school, and today there’s a parking lot where the Lovells’ business stood.

Raymond and Delia Lovell lived in and worked at this building at 513 Union Avenue for about 15 years. The “Lovell’s” sign is visible on the right side of the building, on the second floor. (Knoxville Sentinel)

1920s photo of the Daylight Building, still standing at the northwest corner of Union Avenue and Walnut Street. Lovell’s Massage and Bath Parlor is visible to the far left, the small, darker building with its distinctive flat roof. (Calvin M. McClung Historical Collection)

1913 Lovell’s Baths advertisement. (Knoxville Journal and Tribune)

Around this time, they had been living at two north Knoxville addresses, both on Chicago Avenue, at 188 Chicago in 1909 and 1816 Chicago in 1910. In 1911, however, they moved into their place at 513 Union Avenue and made it both their business and their home for the next fifteen years.

It’s likely that at their new Union Avenue location, Lovell’s Turkish Baths and Treatment Parlors still had separate operating hours for men and women. It’s also likely that they felt they could get more business if both genders could avail themselves of their services at the same time, during all business hours, because in 1914, the Lovells opened a second location at 218 S. Gay Street. A newspaper advertisement announced that “Lovell’s No. 1,” on Union Avenue would henceforth be for women and children only, and “Lovell’s No. 2,” on Gay Street would be for men only. The newest bathhouse and massage parlor was near today’s intersection of Summit Hill Drive and Gay Street.

1922 photo of the New American Bank building at 218 S. Gay Street. For about three years beginning in 1914, this was “Lovell’s No. 2,” the men’s bath and massage treatment parlor. It was located approximately at the present-day intersection of Gay Street and Summit Hill Drive. (Calvin M. McClung Historical Collection)

Although business would continue in two locations for a number of years, in 1917 the men’s treatment parlor moved to 524 Gay Street, and 218 Gay Street was later remodeled into a bank and dentist office. 524 Gay was a prime location, near the intersection of Clinch Avenue and Gay Street, and next door to the Farragut Hotel. Both locations continued to offer the Electro-Turkish and the newer Russian baths, hydrotherapy, Swedish massage, electric light baths and other treatments for which Lovell’s was known.

Lovell’s Electro Turkish Baths, 524 Gay Street. The white building on the right was the Farragut Hotel; today it is the Hyatt Place Hotel on the northeast corner of Gay Street and Clinch Avenue. (Calvin M. McClung Historical Collection)

524 Gay Street, 2024. The little building that housed Lovell’s Electro-Turkish Baths is long gone, but the two buildings on either side remain. (Kevin Bogle)

In 1921, Lovell’s began to advertise its two locations as “Lovell’s Hydropathic Apartments,” but the business would otherwise continue to operate as it had before, until 1927.

The Knoxville Journal ran a news item on July 4, 1926, announcing a new Lovell’s location, with construction well underway. A new brick building was going up at 507 Clinch Avenue, a location formerly occupied by Justice of the Peace Frank Dobson. It was to house not only Lovell’s Hydrotherapy and Massage Parlors, but also the relocated Vegetarian Cafe, a restaurant which had been at 203 Clinch Avenue, at the rear of the Farragut Hotel, since at least 1924. Both businesses would be conducted on behalf of the Layman Foundation, an organization aligned with the Seventh-Day Adventist Church. The Layman Foundation was the financial arm of Madison College, an early 20th-century school, farm, and sanitarium run by the Seventh-Day Adventist Church and located in Madison, Tennessee near Nashville.

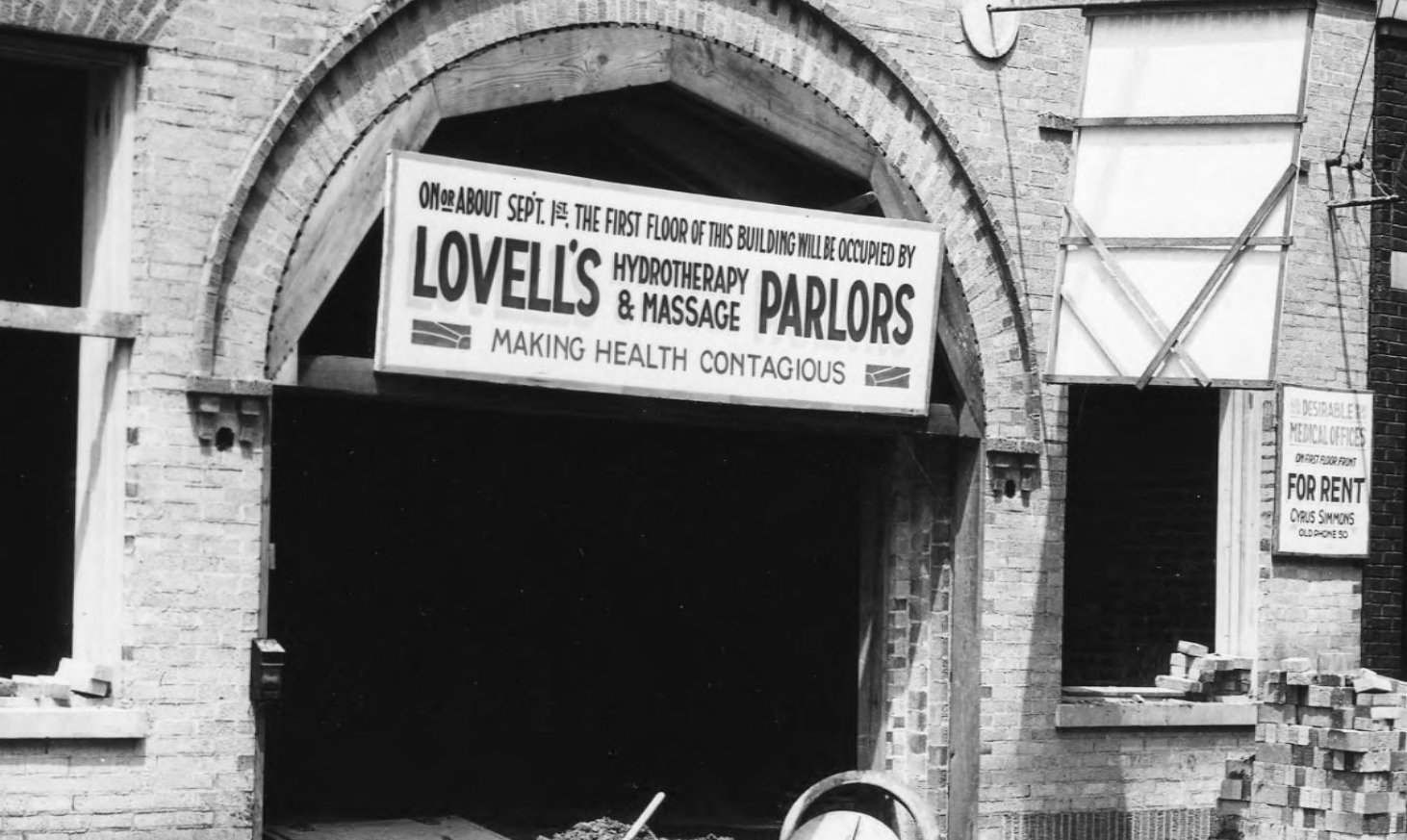

1926 photo of the Layman Foundation’s new building under construction at 507 Clinch Avenue. (Calvin M. McClung Historical Collection)

The Lovells optimistically ran a banner across the front of the construction site on Clinch that said “on or about Sept. 1st, the first floor of this building will be occupied by Lovell’s Hydrotherapy & Massage Parlors- Making Health Contagious.” They evidently missed this deadline, however, as another news item on November 14, 1926 reported that the Lovells were still preparing to move into the building. On a 1927 map of downtown Knoxville, it was labeled the “Good Health Building.”

Close-up view of the building at 507 Clinch Avenue under construction in 1926, with the Lovells’ banner in the entrance archway. (Calvin M. McClung Historical Collection)

Notification of the Lovells’ relocation to 507 Clinch Avenue, 1926. (Knoxville Journal)

Around the same time they announced their new Clinch Street location, Raymond and Delia Lovell moved out of their combination business/home at 513 Union Avenue to a new home at 614 Church Avenue, on the southeast corner of Church and Henley Avenue. This move was apparently in preparation for an even bigger move, as they would only live there for a year before making what was possibly their biggest personal change since their arrival in Knoxville twenty-two years earlier.

On March 14, 1927, the Lovells purchased a house and 19 acres on Valley View Drive in Fountain City, at the time a still-relatively-rural area north of central Knoxville. After settling into their new home, they opened a Turkish bathhouse and massage parlor on the property, probably in a small building that sat next to the house. A natural spring welled up from the ground right next to the house, as well, and it’s likely that they used its waters for their hydrotherapy treatments. Their new home seemingly suited the Lovells well, as a 1976 edition of the Madison College alumni newsletter said of them and their new home, “he and his wife called themselves Adam and Eve and their country home, Garden of Eden.”

After the Lovells closed their treatment parlors at 513 Union Avenue and 524 Gay Street, they focused solely on their Fountain City home and on the Clinch Avenue location for nearly a decade. However, it seems that they closed their last downtown massage parlor around 1935, as no newspaper advertisements for the place ran beyond that year, and the 1936 city directory lists the address as a doctor’s office. The building is still there, at 507 West Clinch, a large block of brick, painted gray with an arched entryway, and it houses an accounting firm.

507 Clinch Avenue, 2024

While Raymond and Delia Lovell were busy with their Turkish baths in Fountain City, their work in Knoxville had also inspired a bigger, more aspirational endeavor. Following their lead, the Layman Foundation had, in 1927, purchased the B. L. Armstrong farm, a 187-acre parcel of land on Lowe’s Ferry Pike (present-day Northshore Drive) eleven miles west of Knoxville. The Foundation’s two stated goals were to grow and provide food for its downtown Vegetarian Cafe and to build a sanitarium on the property. When the purchase was announced, Vegetarian Cafe manager Louis M. Crowder said that “it will be established and operated by a system similar to the large Battle Creek, Michigan sanitariums.”6

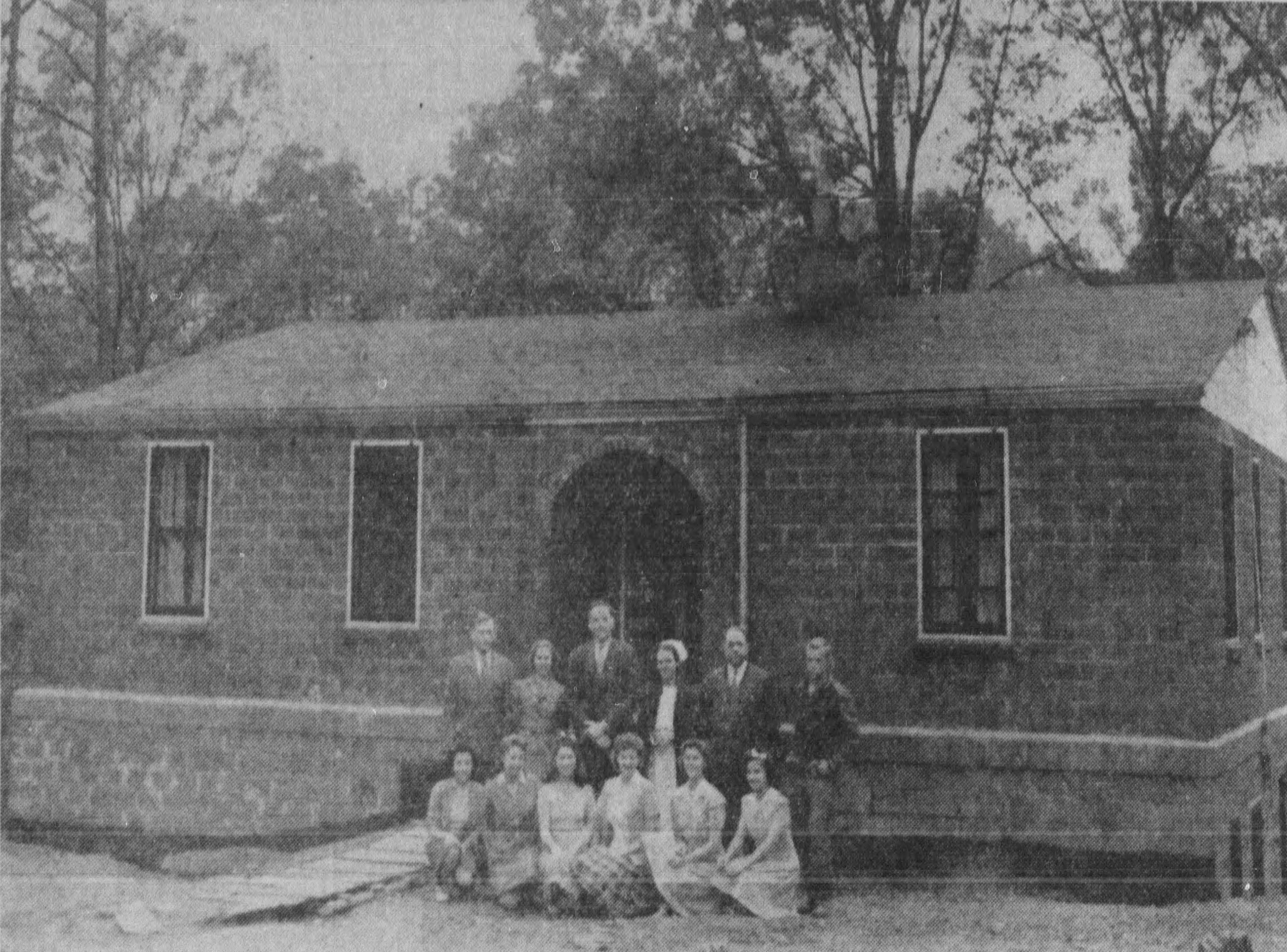

Thus was born Little Creek Sanitarium. The name may have been a play on Battle Creek Sanitarium, and the Tennessee version looked to its Michigan predecessor in many ways. While the Layman Foundation had bought the land in 1927, Little Creek didn’t open until 1940. A 1942 newspaper story says “Little Creek is something of a Little Battle Creek. Like the big Michigan sanitarium, the… endeavor is sponsored by the Seventh Day Adventist laymen. It is one of 53 such schools being pioneered in several Southern states to bring education and health opportunities to children of rural families.”7

1942 photo of the Little Creek Sanitarium school building. (Knoxville News-Sentinel)

Meanwhile, into the 1930s, the Lovells continued to operate their business and offer their massage and bath parlor services from their Fountain City residence, under the name “Lovell’s Health Home.” In 1937, the street they lived on, Valley View Road, was renamed West Adair Drive, to differentiate it from two other Valley View Roads in Knoxville.

1937 advertisement for Lovell’s Health Home. (Knoxville Journal)

It seems that at some point, the Lovells had wound down their business and retired in their “Garden of Eden.” One of their very last advertisements ran in the 1942 Knoxville City Directory.

Delia Lovell died on January 31, 1954 at the Seventh-Day Adventist hospital in Greeneville, Tennessee. She had gone there to visit a friend and apparently suffered a heart attack while she was there. Her obituary said that she had operated the massage portion of their business for 50 years, and she and Raymond had been married for more than 50 years. She was buried at Knoxville’s Lynnhurst Cemetery.

About 11 months after Delia’s death, on December 28, 1954, Raymond A. Lovell sold their home on West Adair Drive, and its accompanying 19 acres, to the Georgia Conference Association of Seventh-Day Adventists. He later left Tennessee for good and settled in Los Angeles, California, to be near his children. Son Frank Bradford Lovell and daughter Dorothy Lovell Charland had both gone west to California years before. Raymond lived to the age of 98 and died on November 6, 1975. At the time of his death, he had been living with his daughter in San Bernardino County. He was buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California.

The Nursing Center at Little Creek is still in operation at its original location in West Knoxville, a legacy of the work the Lovells began when they chose Knoxville over Chicago all those years ago.

Researched and written by McClung Historical Collection Reference Librarian Kevin Bogle

- Bloomberg. (2015, November 16). The legacy of America’s water-cure towns. Bloomberg.com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-11-16/the-legacy-of-america-s-water-cure-towns

- Fanslow, Mary F., “Resorts in Southern Appalachia: A Microcosm of American Resorts in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth centuries.” (2004). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 961. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/961

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024, February 22). John Harvey Kellogg. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Harvey-Kellogg

- Knoxville Sentinel. (April 17, 1911). Woman as Nurse. Newspapers.com. Retrieved March 13, 2024, from https://www.newspapers.com/article/knoxville-sentinel-woman-as-nurse/141746377/

- The Journal and Tribune. (April 16, 1905). 7th day Adventists in Knoxville to Stay 4-16-1905. Newspapers.com. Retrieved March 13, 2024, from https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-journal-and-tribune-7th-day-adventis/143127318/

- The Knoxville News-Sentinel. (May 8, 1927). Little Creek Sanitarium building soon, 1927. Newspapers.com. Retrieved March 13, 2024, from https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-knoxville-news-sentinel-little-creek/142895575/

- The Knoxville News-Sentinel. (November 22, 1942). Little Creek Sanitarium, 11-22-1942. Newspapers.com. Retrieved March 13, 2024, from https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-knoxville-news-sentinel-little-creek/142901565/