“…I knew him [Jesse] well as he was great friends with my husband [James Greenway]. He said he had a wife and some children back in Carolina and he intended, if he ever could, to go back to them. He wouldn’t pay attention to any other woman though he was a good-looking young fellow, and the girls often fell in love with him….”

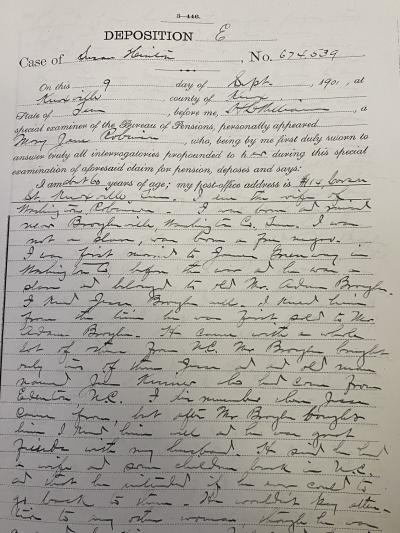

Mary Jane Evans Greenway Robison, Deposition, September 9, 1901

Mary Evans Greenway, a free woman of color who lived near the farmer to which the good-looking young man had been sold during the second or third year of the Civil War, was not alone in her recollection. Twenty to forty years after the fact, those who knew the Corporal named Jesse from Company M, First United States Colored Heavy Artillery still remembered two specific details about him: his remarkable good looks and his extraordinary determination to return South for his wife and children.

“He was a very dark, very handsome fellow with a fine physique,” wrote Courtney Broyles, whose father had purchased Jesse from a “speculator” during the early years of the war.

Per the company sergeant, “Jesse…was very well-made, gentlemanly, and good-looking; he always told me that if he was spared to get out of the Army, he would go back for his wife and children.”

Robert Conner, a fellow member of Jesse’s company and a future commander of Knoxville’s Isham Young Post (c), Grand Army of the Republic, also recalled Jesse’s extremely good looks and build, his skills as a soldier, his good humor, and his popularity, as well as the fact that young women “seemed to get stuck on him” though Jesse had no interest in taking a new wife.

Lewis Broyles, who had been held in slavery on a neighboring farm, described Jesse as “a very fine-looking young man, who would not take another wife because he intended to return to get his wife in South Carolina”, adding “He wasn’t a wild feller at all. He did not curse or drink or play cards. All he did that was not religious was to dance. He was a powerful good dancer.”

Marriages of enslaved persons were recognized as being dissolved not just by death, but also by sale, distance, or any other circumstance that might cause a couple to become separated, so Jesse would have been well within cultural and moral norms to move on to a new wife and/or family. However, such a choice was not within his makeup. Neither was simply staying still and hoping for freedom to come to him.

The handsomeness that Civil war-era East Tennesseans noted and remembered had always been present. As a boy, Jesse was hired out for service as a waiter for hotels in Charlotte, North Carolina, where in addition to learning upper class social skills and cultured speech, he tasted a sample of what life could be like as a free person of color. It was a life he craved, so much so that attempted an escape. His later pension application file only mentions that as a young man, Jesse was permanently returned to the farm.

By the time he was about thirty years old, Jesse’s life had been confined to Capt. Joel Rawlinson’s plantation at Yorkville, South Carolina, approximately forty miles but a whole world away from Charlotte, for several years. During that time, he married and become a father, but he continued to plan for opportunities to seize his own freedom. Building a family had inspired Jesse to expand his plans to include gaining liberty for them as well. He was willing to fight for freedom and even to die in the pursuit of it, if necessary.

At the beginning of the Civil War, emancipation was not a guaranteed outcome nor was the possibility for recruitment of soldiers of color, but Jesse understood that increased opportunities for both could be available, so as soon as news of the firing upon Fort Sumter arrived, he began planning escape with one goal in mind: to deliver his family to freedom as soon as possible. Since his wife Susan and their children belonged to a different owner, widowed Sarah Wallace, Jesse did not fear that they would suffer punishment for an escape on his part, and his gamble seems to have been correct. The danger to himself, though, was immense, whether his journey ended in failure or success. An initial effort resulted in his being hunted down by bloodhounds. Other similar disappointments may have followed. By the second year of the war, Rawlinson’s daughter recalled that “Jesse had become so insubordinate” that her father simply “had to sell him.”

Every enslaved person knew to fear being sold further South as a punishment and possible de facto death sentence. In Jesse’s case, the unexpected occurred when he was purchased by Adam Broyles of Washington County, Tennessee, and his delivery to the Broyles farm brought Jesse almost 200 miles closer to the northern lines he was striving to reach. It also brought him to a community with a long history of belief in the cause of abolition. Freedom (now Limestone), a village named for its high population of free people of color, was less than two miles away from the Broyles farm. Encountering significant numbers of people who were born free and remained so, like Mary Evans Greenway, increased Jesse’s desire for freedom and plans for escape.

Upon hearing word that the 1st United States Colored Heavy Artillery (USCHA) was being raised at Knoxville during the fall of 1864, Jesse felt that his moment had finally arrived. This time, he was successful in his “Grand Escape”, as Courtney Broyles later termed it, guiding several of his fellow enslaved companions to freedom at Knoxville, and in some cases to service in the Union military. Though Lee surrendered in April 1865, Union troops would serve longer, and in the 1st USCHA’s case, that meant until almost one full year later.

Back in Yorkville, Jesse’s loved ones presumed he’d met a dire fate. During January 1866, a letter from Jesse reached his mother, revealing his survival and inquiring about Susan and their children. Instead of writing back on her own, Jesse’s mother took the letter to Susan, who responded herself. She recalled, “Instead of answering my letter, he immediately came himself,” with his army pay and in his military uniform which displayed his corporal’s stripes. While Jesse had enlisted in the army as “Jesse Broyles,” he had long known what he intended his name in freedom to be—Hinton, the surname of his father. Jesse and Susan Wallace Hinton lived together in Charlotte, North Carolina until his death there on May 16, 1886.

Research and writing by McClung Collection Reference Librarian Danette Welch